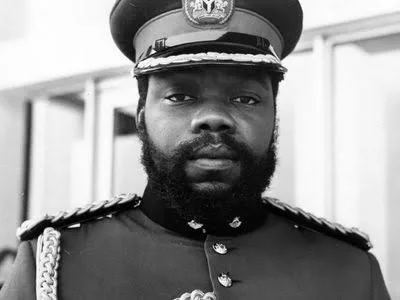

Emeka Ojukwu Biography: Things You Did Not Know About Him

Life And Times Of Dim Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu

Dim Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu was born in the northern part of Nigeria. For a man born of a privileged background that had his life cut out for him and could have spent his life lapping up the luxury arising from his birth, Odumegwu Ojukwu, born on March 4, 1933 at Zungeru, Niger state, chose in early life to chart a different path for himself.

His father, Sir Louis Phillippe Odumegwu Ojukwu, was one of Nigeria’s richest men of his time. Sir Louis, a businessman from Nnewi in present day Anambra State, was a transporter who made his wealth from the boom in the transport sector occasioned by the Second World War.

The young Emeka, barely eleven years old, made headlines when he fought a colonial teacher at his school, King’s College, Lagos, for degrading a black woman. His action earned him a stint in prison from the central authorities. This action must have been one of the reasons that made his father ship him off abroad where he went on to bag a Master’s degree in History at Lincoln College, Oxford University.

On his return to Nigeria in 1956, to his father’s chagrin, he decided to pursue a career outside the family business. His first job waste as an administrative officer in the Eastern Nigerian Civil Service. He was posted to Udi.

Almost one year after joining the civil service, he quit to join the military, making him one of the few graduate Nigerians to join the force. The move was to push him into national and global limelight when years later, he launched the first and only secessionist bid in Nigeria.

In his book “Because I am Involved”, he wrote about his enlistment into the Nigerian Army.

“My enlistment into the Nigerian Army to say the least, startled everybody in Nigeria who heard of it. I went to Zaria and enlisted. I did that mainly because I didn’t want any interference from the well-meaning influence of my father. I joined the Army, signed up, but I wasn’t to be spared the embarrassment because it didn’t take long before my father was aware of it. And he did everything possible to stop the enlistment.

“That is why, despite my educational background, I was not enlisted as an officer cadet. The general idea was that it was agreed between the Governor-General and my father that the best way actually was to let me go into the Army, and I would see for myself what the Army truly was.

“I don’t think that they took into full consideration the level of stubbornness I must have acquired from my father as well, because I remember the question always came to Zaria from Lagos, ‘How is he getting on?”.

With his aristocratic background and education, it did not take him long to rise up ranks. Of the 250 persons in the officer cadre, 15 were Nigerians, with Britons making up the balance.

However, in the lower officer cadre, of the 6,400 people, 336 were British. The late Odumegwu Ojukwu, whose army number was N/29, was resourceful.

Two years after his arrival in Kano, the budding army officer was to be caught in a vortex of politics that had seeped into the military, especially with the exit of the colonial officers on the heels of Nigeria’s emergence as a flag nation after its independence in 1960, and it became a Republic status three years after.

There was growing dissatisfaction in the nation over the conduct of politicians in their struggle for power. This crisis reached a head with the upheaval in the Action Group that was the ruling party in the Western Region, now comprising of the six states in the south-west as well as Edo and Delta states.

This precipitated the first military coup in Nigeria on March 15, 1966 and which was organized by five majors, led by Major Patrick Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu. The coup claimed the lives of one of the parties in the power struggle in the Western Region, Chief Samuel Akintola, who was the Premier, Nigeria’s Prime Minister, Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa and Northern Premier, Sir Ahmadu Bello, among others. The coup was however a flop.

But Odumegwu Ojukwu relied officers and men under his command to support the forces loyal to the head of the Nigerian armed forces, Major-General Aguiyi-Ironsi, who assumed power as head of state.

A few days after he took over the reins of Power, Aguiyi-Ironsi named four officers to head the nation’s four regions. Odumegwu Ojukwu because military governor of the Eastern Region while Hassan Usman Katsina was his counterpart in the Northern Region; Francis Adekunle Fajuyi, Western Region and David Epode Ejoor was governor of Mid-western Region.

Barely four months after the failed coup, there was unrest in the north over the killing of two of its political leaders, Balewa and Bello. People from the Southern part of the country became targets of attacks by the northerners. Hundreds were killed and many buildings belonging to the south-easterners were destroyed. There was hardly any family in the zone that did not lose a member.

As the body bag rose, there was growing angst in the south-east. The mood was retaliatory. However, Odumegwu Ojukwu, who had become a colonel, strived to calm his people. Based on assurances from his counterpart in the north that steps were being taken to end the pogrom and that the safety of those who had not fled the region was guaranteed, he dissuaded his people from embarking on retaliatory attacks. But things worsened.

On 29th July, 1966, the north executed its own counter coup. A group of officers from the area, including Murtala Ramat Muhammed, Theophilus Yakubu Danjuma and Martin Adamu, led northern soldiers in a mutiny. They killed Aguiyi-Ironsi who was on a state visit to Ibadan, the capital of the Western Region along with his host, Fajuyi. Then to accentuate the ethnic colouration of the coup, the masterminds, after two days of talks with Aguiyi-Ironsi’s deputy, Brigadier Babafemi Ogundipe, rejected him as the late head of state’s successor in defiance of military command. Rather, they made Yakubu Gowon, a colonel, the new head of state. Ogundipe who was senior to Gowon was sent to London as Nigeria’s High Commissioner.

In South-Eastern Nigeria, the restiveness arising from the pogrom was yet to abate. Various efforts to douse the tensions failed. As part of the efforts to restore peace in Nigeria, Ghana organised a forum for the leaders from the various regions in the country to meet to talk peace.

The Aburi Peace Conference which held on March 5-7, 1967, the members of Nigeria’s then ruling military junta, the Supreme Military Council (SMC), met for the first time in Aburi, Ghana under the auspices of the then Ghanaian head of state, Lieutenant-General Joe Ankrah. It was the first official meeting of all members of the SMC. Following two bloody army coups in 1966, the military governor of the Eastern Region of Nigeria, Lt-Colonel ‘Emeka’ Ojukwu, had refused to attend any SMC meeting outside the eastern region of Nigeria due to concerns over his safety.

The massacre of tens of thousands of Igbos in Northern Nigeria only heightened Ojukwu’s sense of isolation and insecurity. In turn, Ojukwu’s public belligerence towards FMG (whom he suspected of supporting, or having a hand in the massacres) served to antagonise the FMG, who began to suspect that Ojukwu planned to announce the secession of the eastern region from the rest of Nigeria.

The military governor of the North, Lt-Colonel Hassan Usman Katsina, dismissed Ojukwu’s inflammatory remarks as attempts “to show how much English he knows”. As far as Katsina was concerned, Nigeria’s problem was a stand-off “between one ambitious Colonel and the rest of the country”.

Throughout the six months following the coup of 29th July, 1966, Ojukwu repeated his mantra that,

“I as the Military Governor of the East cannot meet anywhere in Nigeria where there are Northern troops “.

That virtually ruled out an SMC meeting inside Nigeria’s borders. Ojukwu had even turned down offers to attend an SMC meeting on board a British (whom Ojukwu, and Igbos in general did not entirely trust) naval ship, and in Benin City, but was finally convinced to attend in the neutral territory of Aburi in Ghana.

Ojukwu’s aides were not without doubt. Some warned him that the Aburi meeting could be a trap set by anti-Igbo members of the FMG to arrest or kill him. Ojukwu brushed aside their concerns by pointing out that he had received a guarantee of safe passage from Lt-Col. Gowon (then the head of state), and that he had to trust Gowon’s word as an officer and a gentleman.

Virtually everything discussed at that Aburi conference is still relevant today. It is probably the best recorded constitutional debate in history. Aware that something momentous was occurring, the Ghanaians had the conference tape recorded. The tape of the discussions was later released by Ojukwu as a series of six long playing gramophone records. In attendance on the Federal Military Government (FMG) side were Lt-Colonel Yakubu Gowon (head of the FMG), Commodore Joseph Wey (head of the Nigerian navy), Colonel Robert Adebayo (military governor of the Western Region), Lt-Colonel Hassan Usman Katsina (military governor of the Northern Region), Major Mobolaji Johnson (military governor of Lagos), Kam Selem (Inspector-General of Police), Mr. T. Omo Bare, Ojukwu was in attendance as the military governor of the Eastern Region.

The Federal delegation came “wreathed in smiles” and anxious to mollify their former brother-in-arms, Ojukwu. Colonels Adebayo and Gowon even offered to embrace Ojukwu. Ojukwu for his part, was still stung by the terrible massacres of his Igbo kinsmen in Northern Nigeria the previous year and was in no mood to embrace his former colleagues. The contrast in the demeanour of the participants was in itself a microcosm of what took place over the course of the next two days.

While the Federal delegation behaved as if the Aburi conference was a social gathering to reunite former friends who had fallen out over a tiff, Ojukwu saw the conference for what it really was: a historic constitutional debate that would determine Nigeria’s future social and political structure.

As per usual, Western perspective were focused on image, rather than on the genuine problems of the protagonists. Documents recently declassified by the United States’ State Department depicted the FMG-eastern region stand-off as a personality clash between Ojukwu and Gowon. According to the American perspective,

“Many Americans admire Ojukwu. We like romantic leaders, and Ojukwu has panache, quick intelligence and an actor’s and fluency. The contrast with Gowon – troubled by the enormity of his task, painfully earnest and slow to react, hesitant and repetitive in speech – led some Americans to view the Nigerian-Biafran conflict as a personal duel between two mismatched individuals”. (Air gram from US embassy in Nigeria to the Department of State: Lagos A-419,March 11, 1968).

As they were busy fighting in Vietnam and fighting a “cold war” against the USSR, the Americans did not become militarily or politically involved in the dispute. Instead, treating the conflict as one falling within Britain’s sphere of influence.

Although Commodore Wey played an avuncular role, it was obvious that the discussion revolved around younger Colonels: Adebayo, Ejoor, Katsina, Ojukwu and Gowon. Ojukwu showed from the outset that he was prepared for serious business. He arrived with notes, and an army of secretaries. The other debaters should have realised at this point, that something serious was going to occur. The Ghanaian host, Lieutenant-General Ankrah made a few introductory remarks and reminded his guests that “the whole world is looking up to you as military men and if there is any failure to reunify or even bring perfect understanding to Nigeria as a whole, you will find that the blame will rest with us through the centuries”.

Ankrah added that though he understood the eastern region/rest of Nigeria stand-off was an internal matter for Nigerians, they should not hesitate to ask him for any help should they feel the need.

After the hostility and bitterness that preceded the Aburi meeting, the civilian observers were stunned at the camaraderie displayed by the military officers. The debaters threw off formality and addressed each other by their first names: “Emeka”, “Bolaji”, “Jack” (nickname of Lt-Colonel Gowon) were thrown around as if addressing each other at a social gathering.

Ojukwu decided to show his good faith, and to test the good faith of the others by asking all present to renounce the use of force to settle the crisis.

Ojukwu’s motion was accepted without objection. While this request by Ojukwu may sound very Noble, he was in fact, playing a cunning soldier-politician. Ojukwu (despite his boasts of the eastern region’s military prowess) realized that he could not succeed in a military campaign against the far more heavily armed FMG. By getting them to renounce the use of force, Ojukwu was trying to negate the military advantage of the FMG. For he knew that if the political situation eventually got out of control, the FMG would find it difficult to resort to a military campaign having already given their word that they would not use force. This may have been an influential factor in Gowon’s reluctance to engage the eastern region in a full fledged war.

Gowon was even accused by some of his own men for treating Ojukwu with kid gloves. The fiery Lt-Colonel (as he then was) Murtala Muhammed had unleashed his famed volcanic temper on Gowon during an officers’ meeting prior to Aburi. Muhammed slammed his fist down on his desk, and threatened to march into, then sack the eastern region unless Gowon stopped being so soft with Ojukwu.

Murtala was eventually posted to the north, away from Lagos. Despite the leading role he played in the coup that brought Gowon to power, Gowon felt Murtala had been making a nuisance of himself by turning up uninvited at SMC meetings.

At Aburi, the assembled military officers struck a chord in unison on the subject of politicians. All of them voiced out their contempt for the behaviour of civilian politicians whom they blamed the wholesale bloodletting of the previous year (completely ignoring the fact that more Nigerian civilians had been murdered by politically motivated violence, in the one year of military rule so far, than in the preceding five years of civilian democratic rule).

Commodore Wey slammed the point home rather forcefully when he declared that,

“Candidly if there had ever been a time in my life when I thought somebody had hurt me sufficiently for me to wish to kill him it was when one of these fellows (politicians) opened his mouth too wide”.

Ojukwu’s Prophecy

Despite agreeing to attend the conference, Ojukwu was still refusing to recognise Lt-Colonel Gowon as Nigeria’s head of state. Ojukwu had defiantly continued to address Gowon as the “Chief of Staff (Army)” (the post which Gowon occupied before the March counter-coup) in his public statements.

Ojukwu was alarmed at the accession of Gowon to the highest office in the land despite the presence of several other officers who were more senior to him (Brigadier Babafemi Ogundipe, Commodore J.E.A Wey, Colonel Adebayo, Lt-Colonels Hilary Njoku, Philip Effiong, George Kurubo, Ime Imo, Conrad Nwawo and Lt-Colonels Ejoor and Ojukwu who were promoted to Lt-Colonels in the same week as Gowon).

Ojukwu almost prophetically warned that allowing a man backed by coup plotters to become the head of state would create a dangerous precedent which Nigeria would find difficult to emerge from. He told Gowon that “any break at this time from our normal line would write in something into the Nigerian Army which is bigger than all of us and that thing is indiscipline…How can you ride above people’s heads purely because you are the head of a group who have their fingers poised on the trigger?

“If you do it, you remain forever a living example of that indiscipline which we want to get rid of because tomorrow a Corporal will think…he could just take over the company from the Major commanding the company…”

Ojukwu’s warning was of course not heeded and his prediction that junior officers would in the future overthrow their superior officers proved to be correct. The NCOs and lieutenants that shot Gowon to power graduated into the colonels that overthrew him exactly nine years later. As brigadiers, they overthrew the elected civilian government of Shehu Shagari on the last day of 1983, and removed Major-General Buhari from power in 1985. Ojukwu’s impassioned monologue at Aburi could serve as an anti coup plotter thesis.

I also recall that in preparation for Aburi Conference, some of them submitted memorandum. The position of the Eastern Region at that time was that there should be a loose confederation in the absence of true nationalism. At the end of Aburi conference, this was the agreement. When Ojukwu came down from Aburi, everybody hailed him that he did the right thing since the Igbos were no longer wanted in Nigeria.

On the Nigerian part, what was accepted in Aburi was changed overnight, and Ojukwu insisted that “On Aburi we stand”.

Had Nigerians accepted the Aburi conference, there would have been no war. We could have worked together to have a confederation which in my own opinion is the ultimate that can save this nation in the present circumstances.

We should stop pretending, the centralised government was imposed on Nigeria, people were not consulted, it was imposed on Nigeria and we have seen that it is not workable.

All that the rest of Nigeria wants is the oil that is keeping this country together, not the love of one Nigeria. “So on Aburi we stand!”. That was Ojukwu’s position. Then towards July, the series of killings of the Igbos in the north had reached a crescendo that trains loaded with southerners were arriving Enugu the north. In some of the trains, human bodies without heads were loaded and sent to the south.

There was one pathetic case of a pregnant woman whose one eye was plucked out and she was forced at gunpoint to swallow her eye. No eternity would make this woman to forget what was done to her in the name of one Nigeria. That was barbarism the highest level.

Many headless bodies returned to Enugu. Odumegwu Ojukwu had earlier said that the eastern region would not secede from Nigeria unless it was pushed out of Nigeria. But when the headless bodies were coming back and the woman with one eye inside her stomach, plus other atrocities manifested against the south-eastern region, Ojukwu was forced to say, “the push has started”.

And even at that point, Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe, regarded as the father of Nigeria, supported Ojukwu that the push had started. The rest is history. It is significant to note that the words of the Biafra anthem were composed by Dr. Azikiwe himself.

In south-eastern Nigeria, the restiveness arising from the pogrom was yet to abate. Various efforts to douse the tensions failed. A part of the efforts to restore peace in Nigeria, Ghana organized a forum for leaders from the various regions in the country to meet to talk peace. The Aburi peace conference which held in March 1967, did not succeed as the parties did not keep the Aburi agreements. On March 30, 1967, Odumegwu Ojukwu seceded south-eastern region of Nigeria from the rest of the country and proclaimed the area a sovereign state with the name Republic of Biafra.

“Having mandated me to proclaim on your behalf, and in your name, that Eastern Nigeria be a sovereign independent republic, now, therefore, I, Lieutenant-Colonel Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu, military governor of Eastern Nigeria, by virtue of the authority, and pursuant to the principles recited above, do hereby solemnly proclaim that the territory and region know as and called Eastern Nigeria together with her continental shelf and territorial waters, shall henceforth be an independent sovereign state of the name and title of The Republic of Biafra”.

The south-easterners could not have chosen a better man to lead their cause. When on March 6, 1967 Gowon declared war and attacked Biafra, the south-east led by Odumegwu Ojukwu refused to recant. He got support from some foreign nations. After 30 months of civil war in which Gowon, with the support of Britain, Nigeria’s colonial master, used every weapon, including food blockades, which led to massive hunger in the south-east, to humble the Biafrans, their commander knew that his infant Republic would not survive.

On March 9, 1970, Odumegwu Ojukwu who had transformed to a General in the Biafran army, handed over to his deputy, Major-General Philip Effiong, and fled to Cote d’Ivoire. There, Ivorian President Felix Houphouet-Boigny granted him political asylum.

Life In Exile

In Cote d’Ivoire where Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu fled to and sought exile after the Nigerian troops routed the Biafran forces, he sustained the family tradition of successful commerce and married a second wife.

By the end of 1969, it was obvious that Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu and his Biafran troops had lost the war. The Nigerian troops had overrun virtually all the areas that constituted the eastern region and a surrender by the Biafran top command was inevitable. For Ojukwu, the options left to him were clear: surrender and be humiliated by the Gowon-led FMG, whom he regarded as an inferior and junior officer in all respects, or flee into the safe comfort of exile. He chose the latter. Getting accommodation offers from foreign countries was not difficult. Just before the war ended, the Biafran Republic was on the verge of receiving recognition from Ghana, Sierra Leone and Senegal. Then, Houphouet-Boigny of Cote d’Ivoire, Leopold Senghor of Senegal and Siaka Stevens of Sierra Leone had prepared all the political grounds to recognise Biafra.

Sources close to Ojukwu also disclosed that there was also strong sympathy from Switzerland and actually an offer to him to reside there in exile. Of course, he rejected the offer. He opted for Cote d’Ivoire. When his aides asked him why he shunned a country that was more stable in many respects, he replied that he wanted to be nearer home.

So Ojukwu together with some aides and his first wife, Njideka, fled to Cote d’Ivoire on March 11,some hours before Lt. General Philip Effiong announced the surrender of the Biafran troops the next morning. Boigny made available to Ojukwu and his fellow exiles a sprawling compound he had built so his country home in Yamoussoukro.

One of Ojukwu’s aides who lived with him in exile spoke of how the history graduate, a normally restless and active man, suffered from terrible boredom, especially in the early years of that exile experience. None of his kinsmen, no Igbo man ever visited because as the aide argued, of a fear they be victimized by the Federal Military Government of Nigeria. Once in a while, Dr. Akanu Ibiam, former Governor of the eastern region, sent in a note to Ojukwu expressing solidarity. But he, like most other Igbo leaders, never could muster the courage to board a plane to Cote d’Ivoire to physically visit.

The Nigerian intelligence agencies had built up a fearsome machine that had driven quite a scare into Igbo leaders. They were particularly afraid of one man called Muhammadu Yusufu, widely known as M.D. Yusufu, whose main assignment in the Nigerian police then was to seek out and witch-hunt any Igbo person who visited Cote d’Ivoire even for business purposes.

“The mere sight of an Abidjan airport stamp on your passport automatically made you a suspect”, a source said. At a point, even Wole Soyinka was visiting Ojukwu via London rather than directly from Nigeria. To protect the identities of some visitors, the Ojukwu team in collaboration with the Boigny administration, had to devise a strategy called “stop and extract”, whereby Ojukwu was met at the runway immediately the aircraft conveying them landed and spirited away.

It was particularly the job of two young aides residing with Ojukwu at the Boigny villa to pose as Ivorian immigration officers to meet with the visitors as they were disembarking and whisk them away. This strategy shielded visitors from being seen and identified by whoever spies of the Nigerian government that could be lurking at the arrival hall of the Abidjan International Airport, as well as preventing their passports from being stamped by the Ivorian immigration officials.

Despite the strategy, Igbo leaders were not visiting Ojukwu. The best a few o them, like Ibiam, who still had the Biafran zeal burning in them and could draw up the courage, could do to communicate with their former war commander discreetly through letters.

Nnamdi Azikiwe, the first President of Nigeria who never displayed any passion about the Biafra project and had much earlier fled abroad as the first Republic political crisis raged, never to communicate with Ojukwu.

“There was no contact whatsoever from Zik to Ojukwu. No one”, an aide stressed. The aide revealed Ojukwu’s amazement that those who were visiting him regularly in Cote d’Ivoire were members of the radical Yoruba intelligentsia. Professor Wole Soyinka and Dr. Tai Solarin were mentioned as regularly visiting the exiled General at the Boigny villa in Yamoussoukro, and they would stay long hours and nights with him in long discussions.

Gani Fawehinmi was once expected but something somehow happened along the line to the visit. Apart from sellers, the aide stated, many other Yoruba radicals were always in touch with him and giving him advice. After about two years in exile, Ojukwu, seriously troubled by boredom, decided that he had to be active once again. He had been learning French via home teaching, courtesy a teacher generously arranged by Boigny. Within six months, he had become fluent in the language.

Ojukwu was reputed for his general brilliance and his polyglotal capabilities. Before the war, he was eloquent in the three main Nigerian languages. And as an aide said, by the time he finished mastering French, he was sounding more proficient in the language than even in English, which was most remarkable because everybody close to him acknowledged how exceptionally gifted he was with the English garb. He had also decided to send some of his young aides to universities in Cote d’Ivoire and today, those of them alive are effusive in their appreciation to their late master for affording them tertiary education.

For himself, he chose to wade in entrepreneurial waters. The business foray was only confirming him a chip off the old block, and not just an academic and military genius. His father, enjoyed fame throughout West Africa a consummate, highly successful businessman and arguably, in his time, the richest. The platforms for Emeka Odumegwu Ojukwu’s enterprise in exile were three companies – Sereci, Phoenix Africaine and one other. Phoenix Africaine was an outstanding success.

The company engaged in sand filling, dredging and supplies of building materials like and cement to construction sites. Major contracts emanated the Ivorian Presidency and Ojukwu himself was said not to have stepped out from where he was riding or lobbied the any contract. Phoenix Africaine got the contract to build the Hotel de Gulf, one of the best hotels in Cote d’Ivoire. The third company was into aircraft leasing and other aviation services and its greatest client was Libya.

It was also in exile that Ojukwu had his third child from his wife Njideka who came in with their two children born earlier in Nigeria. Unfortunately, it was also there that they separated after Ojukwu began dating Stella, whom he eventually brought in as his wife. Njideka returned to Nigeria in anger. Even there in exile, Ojukwu never hid the fact that he loved beautiful women and that was how Stella came in.

His aide reminisced that whenever anybody questioned Ojukwu about his love for pretty ladies, he would humorously reply, “Do you want me to be homosexual?”. After living in exile for more than ten years, Ojukwu began yearning to go home. Some members of the new political class which had taken off in 1979 began to get in to with him to leverage whatever popularity they believed he had in Igboland to win Igbo votes. The Great Nigeria People’s Party actually announced him as its candidate for a House of Representatives seat in Anambra State when then Head of State, Olusegun Obasanjo, had not pardoned Ojukwu to allow him to return to Nigeria.

In 1982 when Alhaji Shehu Shagari had become Executive President, George Obiozor and Chuba Okadigbo visited Ojukwu and finalized talks on his homecoming.

Odumegwu Ojukwu spent 13 years in exile before President Shehu Usman Shagari, during the second Republic granted him official pardon. With his pardon, he returned to Nigeria in 1982, to a heroic welcome. No sooner had he returned to Nigeria than he joined politics. Ojukwu became a member of the ruling National Party of Nigeria, leading credence to rumours that his pardon had political undertones.

Nigeria was on the cusp of another general elections and the race was expected to be keen. Given his charisma among his people, his membership of NPN was to garner more for the party in the south-east. His foray into politics was shortlived in the second Republic. He lost his bid to the senatorial ticket of the party. About a year after his return, the second Republic ended following a coup that produced Major-General Muhammadu Buhari as head of state.

Odumegwu Ojukwu was among politicians detained and subsequently jailed by the Buhari junta. Freedom however, came for him about two years later when General Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida, in a palace coup in 1985, overthrew Buhari and reviewed his prison terms and charges.

His short romance with NPN kindled his interest in politics. He was of the 1995 Constitutional conference that was supposed to midwife the fourth Republic. He remained an unabashed Igbo irredentist, replying his critics that he was first an Igbo before being a Nigerian. After the return of democracy in 1999, Odumegwu Ojukwu became the leader of the All Progressives Grand Alliance, a party whose sphere of influence remains within his former Biafran enclave, the south-east.

His obstinate nature also manifested in his romance with former beauty queen, Bianca Onoh, daughter of second Republic governor of old Anambra State, Chief C.C. Onoh. Despite opposition from his father-in-law, Ojukwu to change his mind about the beauty queen. Both went ahead to get married despite opposition from Onoh. It took years for the former governor to come to accept Odumegwu Ojukwu a son-in-law.

When prominent Igbo leaders converged in Enugu to celebrate Ojukwu’s 78th birthday, little did they know that they were engaging in a last dance the Igbo leader, who was then in a London hospital. They never had any premonition that “Ezeigbo Gburugburu” as he was fondly called, was spending his last days on earth. Months earlier, he had been rumoured dead. It took assurances from one of his sons, Okigbo to dispel the death rumour. “It is not true that my father died” he said.

Like another prominent Igbo leader and Nigeria’s first President, Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe, Odumegwu Ojukwu read his obituary alive.

Death of Ojukwu

Ojukwu lost his life’s struggle in 2011 at London after a brief illness and the Nigerian Army accorded him the highest military accolade and organized for him a funeral parade on in Abuja. He was buried at his compound in his home town Nnewi, Anambra State.